|

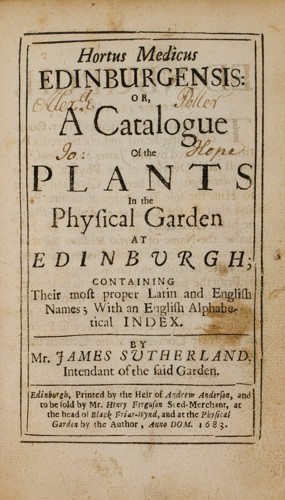

[Narrator] In 1670, two doctors in Edinburgh began to collect plants for medicine and teaching. 350 years later, 1 million people enjoy a visit to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and it's three regional gardens every year. Places of great beauty. Plants from over 150 countries. The mission of the garden is to explore, conserve and explain the world of plants. A walk with experts is a good way to look and learn. |

|

[David Knott, Curator Living Collection] So Kirsty, this is one of our three and a half thousand trees. This is a UK and Ireland champion Chinese wingnut, Pterocarya macroptera var delavayi and it's a UK and Ireland champion, both for its girth and for its height. |

|

[Kirsty Wilson, Horticulture] Collected by George Forrest, one of the famous Scottish plant hunters and of great association here at the Botanics. |

|

[Narrator] Many plant species in the collection are threatened or even extinct in the wild. Plants from China to the Cairngorms are being conserved here so they can be reintroduced to native habitats. The Garden's scientists work in 35 countries across four continents, partners in key conservation projects. |

|

[Mark Hughes, Science] William Jack described dozens of new species, but all of his specimens were lost, but his manuscript from 1822 survived, so we followed in his footsteps and refound these things that we thought were lost for nearly two centuries. |

|

[Narrator] The garden's education programmes train the botanists and horticulturists of the future, increasing the interest that people take in plants is also a major focus. |

|

[David Tricker, Horticulture] So these are pollinated by bumblebees, and it's called buzz pollination. So you'll hear that the bee land on the flower and they'll go and free the pollen from inside. But they also go to the females. Now females have nothing to give to the bees at all. They smell the same and they look the same. So the bees will fly after the female flower thinking they're gonna get more pollen, but then realise last minute and kind of go and pull back. |

|

[Rebecca Yahr, Science] I think the Botanics has a huge role to play in education and outreach. It's a big part of my job and it's a big part of what we do, to try to celebrate these habitats, to try to bring them to people and to try to explain why they're interesting and special, why we need to protect them. |

|

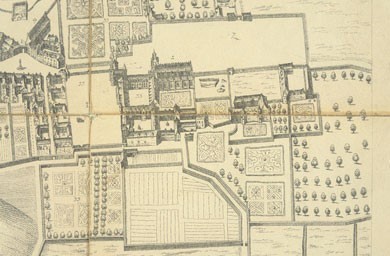

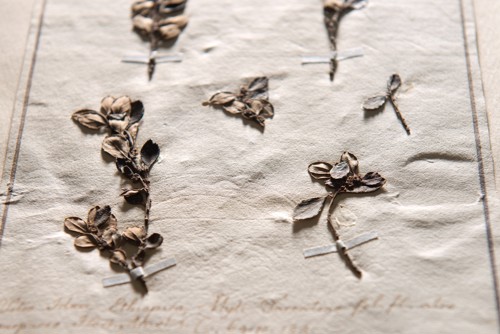

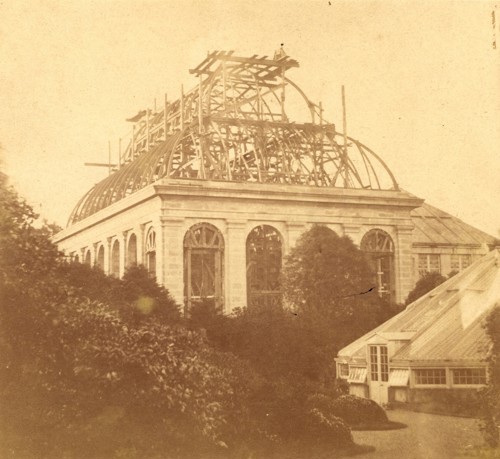

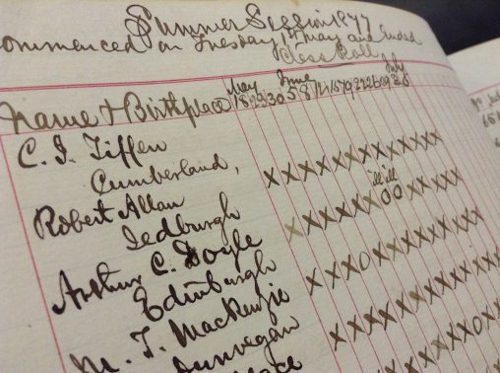

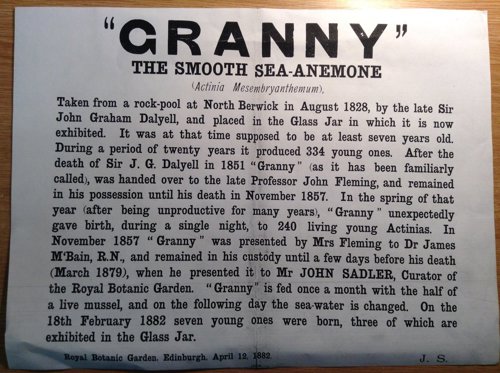

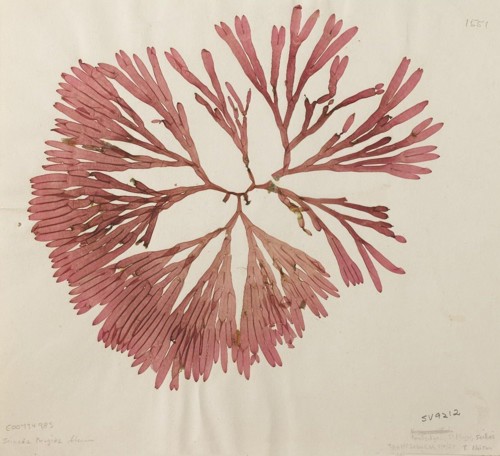

[Narrator] The Royal Botanic Garden moved to its present home at the heart of Edinburgh in 1820. Valuable books, fine works of botanical art and manuscripts form part of Scotland's national collection for botany and horticulture. Centerpiece to the preserved collection, is the Herbarium. In a single building, 3 million dried specimens, many centuries old. Their value to research will last well into the future. |

|

[Tiina Särkinen, Science] These are long term banks of knowledge that we really have privilege to look after. Thanks for the brave person who in 1830 collected this wild potato species in Chile, now we have these samples. Did he ever imagine it would be used in the way that we're planning? I don't think so. |

|

[Narrator] In future, with further advances in sequencing technology, scientists will be able to sequence the entire genome of specimens from the Herbarium, paving the way for research into topics such as climate change and plant health. A newly created rain garden shows visitors how to take on climate change. |

|

[David Knott] It's just been newly planted with a range of Scottish natives and exotic perennial species to see which plants cope best. |

|

[Kirsty Wilson] And I suppose this shows to many of the visitors that come into the Botanics what they can create in their own home in a rain garden that can absorb and capture that water. |

|

[David Knott] And I think that's gonna be an important challenge for people in this part of the world, but also more widely across other parts of the world, as to how we mitigate the impacts of climate change. |

|

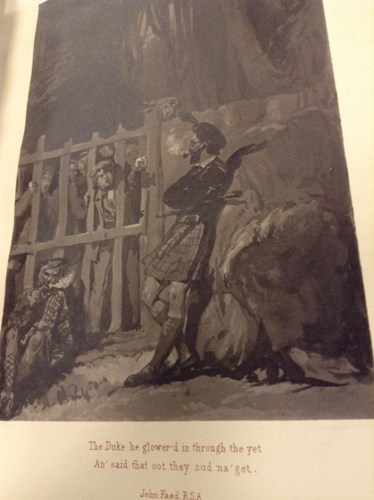

[Narrator] The Botanic Cottage was built in 1764, lovingly restored in 2016, it's the hub of the community programme, which aims to promote health and wellbeing. |

|

[School child] Oh look, I found a potato. [Teacher] Oh, fantastic Frank. Ah, fantastic. |

|

[Narrator] School visits are a way for young people to grow in self-confidence. [Cath Ashby, Education] It's a really nice colour, isn't it? Everybody can enjoy a garden. It doesn't distinguish between abilities or ages or your level of wealth or anything. Everybody can enjoy a garden. |

|

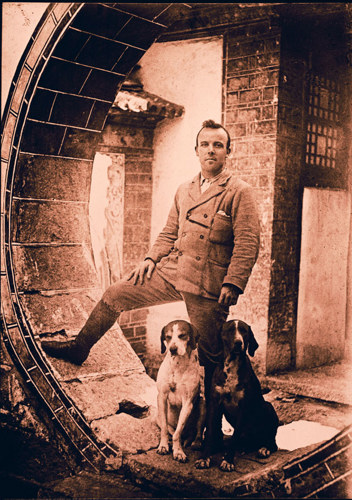

[Narrator] At this 350th anniversary, the people of the Royal Botanic Garden look ahead while proud of their history. |

|

[Katy Hayden, Science] To sit in the Professor's Room in the Botanic Cottage, which is the oldest intact classroom from the Scottish Enlightenment is a feeling like no other. |

|

[Louise Galloway, Horticulture] We're still naming one new species each week. It's mind blowing, the fact that we're still discovering new species and it makes it so important that we protect the world's natural habitats. |

|

[Simon Milne, Regius Keeper] These, they're well cropped roses, aren't they? This is a very exciting time for the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. We are very well positioned to take on these new challenges with our expertise, with our collections. For me, it's an enormous privilege to be leading the whole organisation. And so I'm actually optimistic about the future, because although of course, climate change and biodiversity loss are major threats. There are answers and some of the answers lie here in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. |